Labradors retrievers are pigs. Well, that’s not right. They’re dogs, but it does seem like there’s nothing they won’t eat, nothing is ever enough, and there’s no bad time to have food, from the bowl or from the human’s plate, hand or off the floor. And like almost every behavioral “quirk”, it’s in the genes.

Eleanor Raffan from the University of Cambridge conducted a genetic study of the breed, with the results appearing in Cell Metabolism.

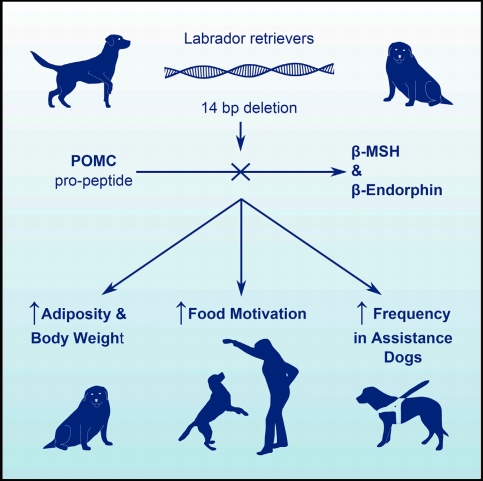

Raffan and her team analyzed genetic profiles of different labradors: 15 obese and 18 lean ones. Three obesity genes were analyzed, and one gene in particular stood out. The POMC gene.

Among the obese labradors, this specific gene seemed to be a bit messed up. They were unable to produce special appetite suppressing neuropeptides; small, protein-like molecules that are involved in switching off feelings of hunger after eating a meal. These dogs stayed hungry, even after a big bowl of food. The mutation was absent from other breeds, except for the flat-coat retriever.

The team also took a look at a larger sample of 310 labrador retrievers, noticing a significant number of canine behaviors which are associated with the “messed up” POMC gene. Not all of the labradors with the variation in their DNA were fat, but it was easy to associate the mutation with higher weight. The dogs with the impaired gene displayed more food motivated behavior: frequent begging, attentive during meal time, scavenging for leftovers and scraps. On average, the POMC deletion was associated with a 4.4 pound (2 kg) weight increase.

Raffan: We’ve found something in about a quarter of pet labradors that fits with a hardwired biological reason for the food-obsessed behavior reported by owners. There are plenty of food-motivated dogs in the cohort who don’t have the mutation, but there’s still quite a striking effect.

About one in four labradors have this mutation, and the same can be said of flat-coat retrievers, so it means that POMC isn’t the only factor. What is interesting is that the mutation was found in three out of four assistance dogs. It does make sense: Their inability to resist food makes them more easy to train, hence their inclusion in assistance training programs.

There are also potential implications for treating human obesity. The canine POMC gene works similarly in humans, unlike the way it functions in rats and mice. One of the senior authors on the study said further research in these obese Labradors may not only help the well-being of companion animals, but also carry important lessons for human health.

Dogs with the POMC mutation don’t have to be obese. It’s up to the owner to be strict about portions and not let their cuteness fool them. Those puppy eyes might be tough to resist, but it gets easier saying no with time for new dog owners, and in the long run, it’ll keep your dog healthier and probably with you for a bit longer.